Prairie City State Vehicular Recreation Area (PCSVRA) is home to one of California's rarest and most threatened freshwater ecosystems — vernal pools. These ancient, seasonally flooded wetlands beautifully mirror the rhythms of nature, undergoing remarkable transformations during each phase of their annual cycle. Vernal pools at PCSVRA sustain a diverse community of native plants, animals and other living organisms, including the federally endangered vernal pool tadpole shrimp.

Please enjoy this short video highlighting PCSVRA’s vernal pools. Click on the links below to learn more.

Prime examples of vernal pools at Prairie City SVRA (PCSVRA) are found within shallow depressions on the surface of the park’s annual grasslands, where vehicular use is excluded. The mysterious contours of these otherwise gently sloping landscapes are defined by hundreds of dome-shaped earthen mounds, which rise several feet above the surrounding terrain, like frozen waves in a sea of grass. It’s in between these raised mounds of earth, known as Mima mounds, that the shallow surface depressions exist.

Underlain by a hard layer of clay know as hardpan, these surface depressions function much like clay bowls, preventing rainwater from draining down into to the subsoil. During the cool, wet months of winter and spring, rainwater fills and becomes trapped in the surface depressions, forming vernal pools. As spring gives way to summer, the vernal pool waters evaporate, leaving the drying surface depressions blanketed in lush, multicolored ribbons and rings of wildflowers. During the hot, dry months of summer, the surface depressions appear scorched and sunbaked.

Though they occur in an assortment of shapes and sizes, vernal pools are generally no larger than a few tenths of an acre (think the area between the goal line and the 30-yard line of a football field). Rarely do vernal pools exceed a foot in depth. During extended periods of drought, vernal pool surface depressions may remain dry all year.

Vernal pools sustain an incredibly diverse community of native plants, animals and other living organisms, many of which have adapted over hundreds of thousands of years to survive only in these seasonally flooded wetland ecosystems. In fact, the vernal pools at PCSVRA provide habitat for two rare species of freshwater crustaceans: the vernal pool tadpole shrimp and the vernal pool fairy shrimp. These creatures are direct descendants of some of the oldest known living species on Earth. Faced with the threat of extinction due to accelerated habitat loss—driven largely by agricultural development and urbanization—the vernal pool tadpole shrimp and the vernal pool fairy shrimp are protected under the federal Endangered Species Act.

Vernal pools exist in just a few places on Earth. It takes the right type and combination of natural surface features, soils and climate for vernal pools to occur. And here at PCSVRA, our rolling grasslands, with their raised mounds of earth and shallow surface depressions; our annual grassland soils, with their hard layers of clay that exist just below the surface of the landscape; and our Mediterranean climate, which cycles from hot and dry to cool and wet—all of these natural features combine to create our unique and rare vernal pool wetlands.

The presence of water is the defining characteristic of the vernal pool wet phase—one of three phases in the vernal pool cycle. From roughly November through March, rainwater fills and remains trapped in shallow depressions on the surface of Prairie City SVRA’s annual grasslands, forming vernal pools. As vernal pool waters accumulate, life is awakened in previously dormant seeds and eggs of plants and animals that have adapted to survive in the harsh, wet-dry conditions of these seasonally flooded wetland ecosystems. These water-dependent organisms scramble to mature and reproduce before the shallow surface depressions again become dry.

As spring gives way to summer, warmer temperatures and drier atmospheric conditions cause the vernal pool waters to evaporate. As the waters recede, visually stunning ribbons and rings of wildflower blooms form in and along the margins of the drying surface depressions, punctuating the otherwise green grasslands with dazzling shades of yellow, purple, pink and white. These wildflower shows define the vernal pool flowering phase.

During the summer months, when temperatures here soar into the triple-digits, and any hint of rain is still months away, the surface depressions dry completely, marking the vernal pool dry phase. Many rare species of plants and animals that exist only in California’s vernal pools produce seeds and eggs that are equipped to lie dormant in the dry beds of the surface depressions for many years, until the right conditions to sprout or hatch occur. These evolutionary adaptations allow the species to survive even through fire and extended periods of drought.

As winter and spring rains return, the eggs hatch, the seeds sprout and the seasonal cycle of vernal pool flooding, flowering and drought begins anew.

Vernal pools at Prairie City SVRA (PCSVRA) exist in shallow depressions on the surface of the park’s annual grasslands. These seasonal wetlands are believed to be tens of thousands of years old. Elsewhere across California, the oldest vernal pools are thought to have formed hundreds of thousands of years ago. Exactly how PCSVRA’s vernal pools originated remains somewhat of a scientific mystery.

Lying just below the surface of PCSVRA’s annual grasslands is a hard layer of clay, known as hardpan. Hardpan prevents seasonal rainwater from draining down into the earth’s subsoil. Developed over millions of years, hardpan is the result of a complex combination of natural processes. These include weathering, erosion and the eventual deposition of sand and gravel from the Sierra Nevada to the Central Valley via rivers and streams. During the cool, wet months of winter and spring, a perched water table forms above the hardpan, saturating the surface layer topsoil.

Less understood are the origins of hundreds of dome-shaped earthen mounds, known as Mima mounds, which dot PCSVRA’s annual grasslands with striking symmetry. Mima mounds are found in annual grasslands across certain parts of the western half of the North American continent and in other parts of the world. They form where hard, subsurface soil layers obstruct naturally occurring drainage. Their association with vernal pools, however, is largely restricted to those that exist in California’s Central Valley. Its characteristic Mediterranean climate—which cycles from hot and dry to cool and wet—is an essential factor in the formation of these seasonal wetland ecosystems. Viewed from higher elevations, the appearance of Mima mounds resembles frozen waves in a sea of grass.

Scientists have puzzled over the formation these strange surface features for more than a century. Numerous theories have been proposed to explain their existence, including earthquakes, erosion and glacial activity. In recent years, the prevailing hypothesis suggests that Mima mounds are formed by pocket gophers. These burrowing rodents exist largely underground, creating and maintaining elaborate networks of tunnels, where they live mostly solitary lives.

Some scientists speculate that pocket gophers work underground during the dry season to pile loose soil high above the perched water table. This theory suggests that pocket gophers build Mima mounds as elevated shelters to avoid drowning in the saturated, surface layer topsoil during the cool, wet months of winter and spring.

PCSVRA’s shallow grassland surface depressions form in low lying saddles, or troughs, of soil, which connect adjoining Mima mounds. During the wet season, rainwater fills and becomes trapped in these surface depressions, forming vernal pools. Decaying plant matter, or detritus, washes into vernal pools from adjoining Mima mounds. This nutrient-rich detritus serves as a critical food source for the diverse community of organisms that depend upon vernal pools for their survival.

Prairie City SVRA’s (PCSVRA) vernal pools and the annual grasslands in which they exist provide food, shelter and space for an incredibly diverse community of native plants, animals and other living organisms to grow, develop and reproduce. Many of these species have adapted over hundreds of thousands of years to survive only in the harsh, wet-dry conditions of California's ancient vernal pools, which alternate between extended periods of flooding and drought.

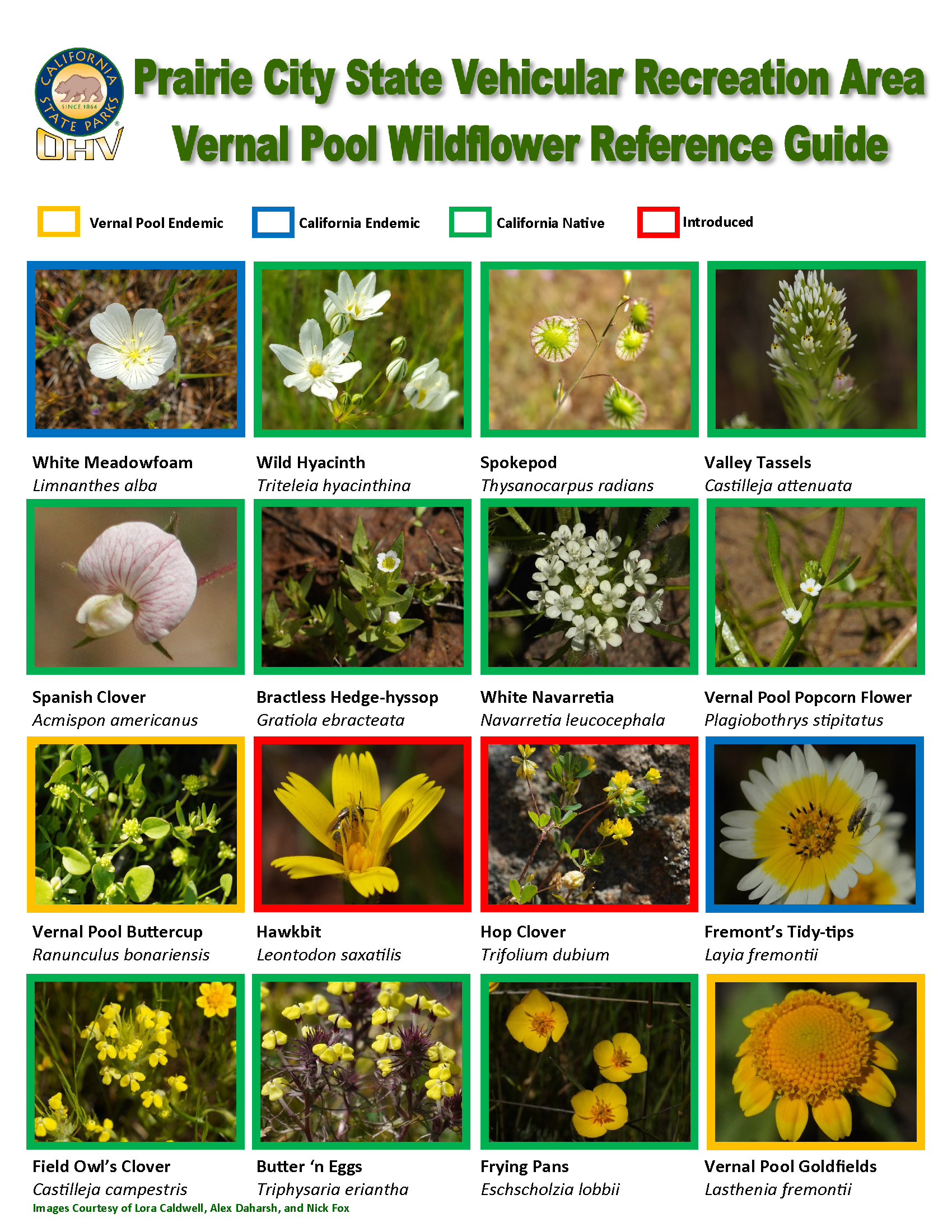

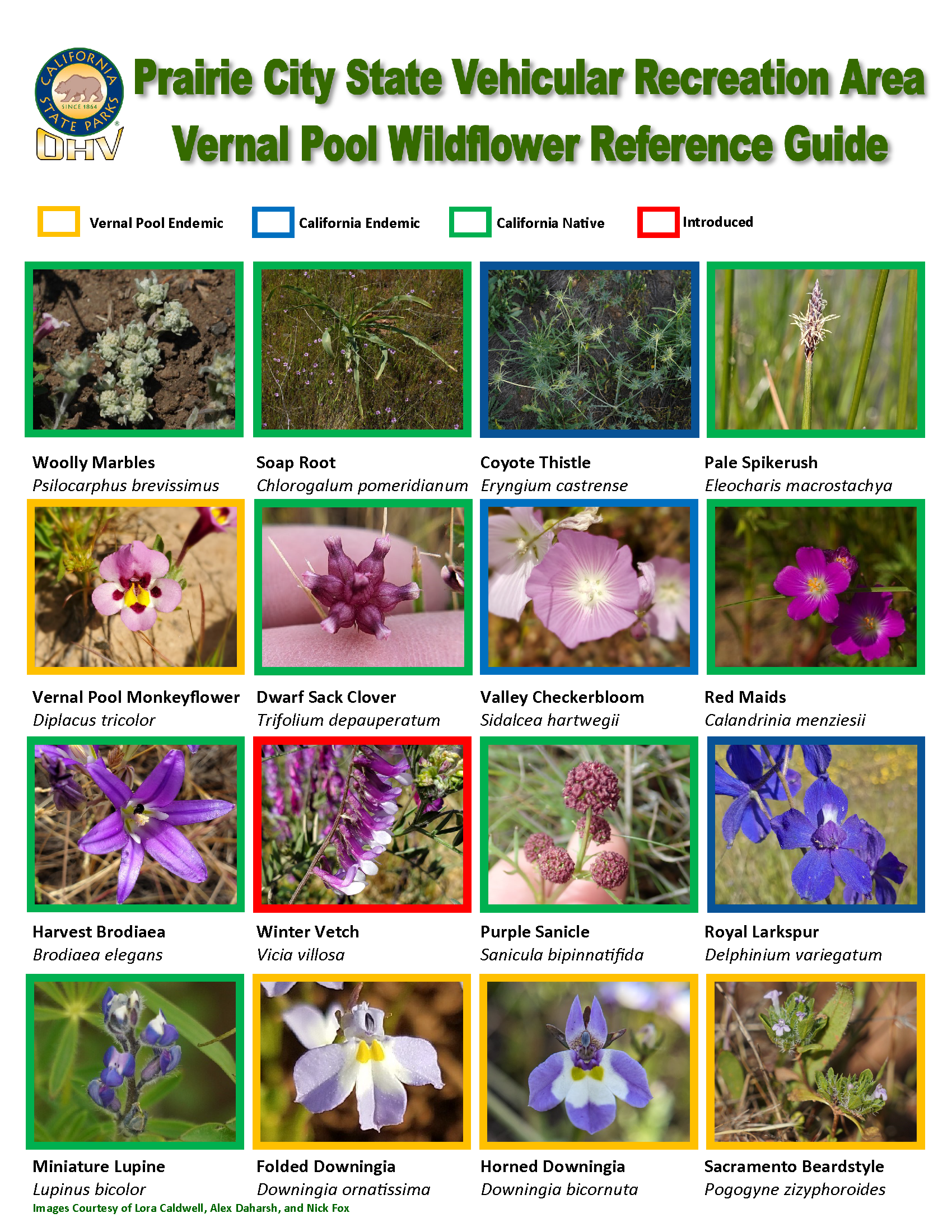

Though non-native plant species frequently invade and may ultimately come to dominate the upland vegetation of California’s annual grasslands, most plant species that thrive in the low-lying vernal pool surface depressions are native to the state. In fact, many of these native plants exist only in, or are endemic to, California’s vernal pools, and are found nowhere else in the world. Unlike endemic plant species, non-native plants—which were first introduced to California’s Central Valley grasslands by Spanish settlers over 250 years ago—have not adapted to survive in the extreme, wet-dry conditions of vernal pools.

Endemic plant species such as royal larkspur, Fremont’s goldfields, horned downingia, frying pan poppy and valley checkerbloom can all be found blooming in and around PCSVRA’s vernal pools from March to June. During the vernal pool flowering phase, magnificent, multicolored ribbons and rings of these plants’ flashy wildflowers blanket the drying vernal pool surface depressions.

Decaying plant matter, or detritus, that washes into vernal pools from adjoining Mima mounds serves as a critical, nutrient-rich food source for a host of aquatic insects and invertebrates, including the federally endangered vernal pool tadpole shrimp. This ancient, freshwater crustacean is found in only a fraction of vernal pools throughout California, including those at PCSVRA. The vernal pool tadpole shrimp is a direct descendant of one of Earth’s oldest known living creatures, Triops cancriformis. It is referred to as a “living fossil” because its appearance is nearly identical to that of its ancient ancestors. The omnivorous vernal pool tadpole shrimp feeds also on other freshwater crustaceans, including the federally threatened vernal pool fairy shrimp.

Because the grassland surface depressions in which they form remain dry for much of the year, vernal pools are incapable of supporting fish. Because fish prey on aquatic invertebrates in year-round wetland habitats, their absence from vernal pools explains why creatures like the vernal pool tadpole shrimp thrive in these seasonal wetland ecosystems.

Vernal pools also provide resources that attract and sustain all manner of birds, including waterfowl, wading birds, shorebirds and songbirds. Plant seeds, aquatic insects and invertebrates serve as critical food sources for migratory birds seeking rest in and near vernal pools. Red-winged blackbirds, killdeer and great egrets are just a few of the many bird species commonly seen foraging, nesting and hunting in and around Prairie City SVRA’s vernal pools, particularly during the cool, wet months of winter and spring.

Burrowing pocket gophers, which are believed to be responsible for building the elevated Mima mounds that dot Prairie City SVRA’s annual grasslands, have diets that consist entirely of plant matter. These small mammals in turn serve as food sources for other mammals, reptiles and raptors, including coyotes, gopher snakes and Swainson’s hawks, all of which thrive near PCSVRA’s vernal pools.

For hundreds of thousands of years, millions of vernal pools are believed to have existed across California’s Central Valley. In less than 200 years, 90 percent of California’s ancient vernal pools have been lost forever, due in large part to agricultural development and urbanization, and, to a lesser extent, surface mining.

During the first half of the 20th Century, hulking mechanical dredgers ripped gold from ancient riverbeds underlying large tracts of land that we now know as Prairie City SVRA (PCSVRA). Heaps of discarded cobblestones, known as dredge tailings, are presently strewn across large sections of the park, where vernal pools once existed—distinct reminders of these ecologically destructive operations.

Today, only a fraction of the park’s ancient vernal pools remain. By recreating exclusively on designated trails, tracks and obstacles, PCSVRA’s diverse community of OHV recreationists play a critical role in preserving and protecting these vernal pools and the equally diverse community of creatures that depend on them for their survival.

Staff-led tours of PCSVRA’s vernal pool management areas are conducted in the spring, allowing visitors to experience firsthand the splendor of these rare and rapidly disappearing seasonal wetland ecosystems. Please check PCSVRA’s website and follow the park’s official Instagram account for information concerning these tours.

Barry, Sheila. Managing the Sacramento Valley Vernal Pool Landscape to Sustain the Native Flora. UC Cooperative Extension, 1998.

<https://vernalpools.ucmerced.edu/sites/vernalpools.ucmerced.edu/files/page/documents/

3.6_managing_the_sacramento_vernal_pool_landscape_to_sustain_native_flora_by_sheila_j._barry.pdf >

Barry, Sheila. Rangeland Oasis. University of California Cooperative Extension, 1995.

<https://ucanr.edu/repository/fileaccess.cfm?article=157404&p=xxwgmw>

Brittan, Martin R., Ph.D. Spring 1996 Vernal Pool Survey at Prairie City State Vehicular Recreation Area. Michael Brandman Associates, 1996.

California Chaparral Institute. Vernal Pools. <https://www.californiachaparral.org/chaparral/vernal-pools/>

California Department of Fish & Wildlife. Native Plants and Invasive Species.

<https://wildlife.ca.gov/Conservation/Plants/Invasives>

California Department of Fish & Wildlife. California’s Vernal Pools. June 17, 2013.

<https://wildlife.ca.gov/conservation/plants/vernal-pools>

California Department of Fish & Wildlife, California Vernal Pool Assessment Preliminary Report.May 1998.

<https://nrm.dfg.ca.gov/FileHandler.ashx?DocumentID=99964>

California Native Plant Society. Rare Plant Program, Inventory of Rare and Endangered Plants of California (online edition v8-03 0.39). 2020.

<http://www.rareplants.cnps.org/>

Final General Plan, Prairie City SVRA, Sec. 2-66. September 2016.

<https://www.parks.ca.gov/pages/21299/files/Prairie-City-Final-General-Plan_9_%202016.pdf>

Gabet, Emmanuel J., & Perron, Taylor J., & Johnson, Donald L. Biotic Origin for Mima Mounds Supported by Numerical Modeling. Geomorphology (206), 2014.

< https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0169555X13004765>

Garvin, Cosmo. Losing the Life Aquatic.Sacramento News & Review, April 18, 2013.

<https://www.newsreview.com/sacramento/losing-the-life-aquatic/content?oid=9620411>

Jones & Stokes Associates. Vernal Pool Resources at Prairie City State Vehicular Recreation Area (Final Report).1994.

Kruckeberg, Arthur R. California Natural History Guides: Introduction to California Soils and Plants. University of California Press, 2006.

Sacramento Splash. About Vernal Pools.<https://www.sacsplash.org/about-vernal-pools>

Sacramento Valley Chapter, California Native Plant Society. Vernal Pools: More than Just “Rain Puddles.”

<https://www.sacvalleycnps.org/conservation/vernal-pools>

Smith, David W., & Verrill, Wayne L. Vernal Pool-Soil-Landform Relationships in the Central Valley. USDA; Jones & Stokes Associates, 1998.

<http://www.vernalpools.org/proceedings/smith.pdf>

Stevens, Vanessa. & Holzman, Barbara, PhD. The Biogeography of the Vernal Pool Tadpole Shrimp (Lepidurus packardi). Geography 316: Biogeography, San Francisco State University, 2003. <http://online.sfsu.edu/bholzman/courses/Fall%2003%20project/lpackard.htm>

Solano County Water Agency. Vernal Pool Tadpole Shrimp. July 2012.

<https://www.scwa2.com/documents/hcp/appendix/H-6.Vernal%20Pool%20Tadpole%20Shrimp.pdf>

The National Wildlife Federation. Pocket Gophers.< https://www.nwf.org/Educational-Resources/Wildlife-Guide/Mammals/Pocket-Gophers>

The Natomas Basin Conservancy. Vernal Pool Tadpole Shrimp.

<https://www.natomasbasin.org/education/the-nbhcp-species/wildlife/vernal-pool-tadpole-shrimp/>

University of California, Merced. Fairy Shrimp of the Merced Vernal Pools and Grassland Reserve.

<https://vernalpools.ucmerced.edu/ecosystem/reserve-fairy-shrimp>

US Bureau of Land Management. Chapter Introduction: Vernal Pools.<https://www.blm.gov/sites/blm.gov/files/tablerocks_vernal_intro.pdf>

US Environmental Protection Agency. U.S. EPA Settles Case over Destruction of Rare Central Valley Wetlands – Agreement will Preserve Unique California Habitat. August 14, 2014.

<https://archive.epa.gov/epapages/newsroom_archive/newsreleases/50abf9d34b25028385257d34005a64e3.html>

US Environmental Protection Agency. Vernal Pools. <epa.gov/wetlands/vernal-pools>

US Fish & Wildlife Service. 5. Vernal Pool Tadpole Shrimp (Lepidurus Packardi). September 2005.

<https://www.fws.gov/sacramento/es/recovery-planning/vernal-pool/documents/vp_tadpole_shrimp.pdf>

US Fish & Wildlife Service. US Federal Register, 50 CFR. Part 17, Vol. 68, No. 151, Final Designation for Critical Habitat for Four Vernal Pool Crustaceans and Eleven Vernal Pool Plants in California and Southern Oregon. Final Rule. August 6, 2003.

<https://www.fws.gov/sacramento/es/Critical-Habitat/Vernal-Pool/Acreage/Documents/fr4160.pdf>

Witham, C. W., & Mawdsley, K. Jepson Prairie Preserve Handbook, 3rd Edition. Solano Land Trust, 2012.

Click to Enlarge

Click to Enlarge Click to Enlarge

Click to Enlarge Click to Enlarge

Click to Enlarge

Click to Enlarge

Click to Enlarge

Click to Enlarge

Click to Enlarge Click to Enlarge

Click to Enlarge